Parmesan cheese has been around for a long time. We put it on a bunch of our favorite stuff, from pasta to risotto, to pizza and more.

This article will cover important basics of it like nutritional information, history, what you can make with it, and anything else I can find that might be helpful to know about parmesan cheese.

Nutrition Facts for Parmesan Cheese

Let’s be honest, half the reason that you probably searched for it was because you wanted the nutritional content. Maybe I’m wrong about that, but either way, here it is! These are the nutrition facts for a hard wheel of the stuff, so not grated. That’ll be below.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

| Energy | 392 calories (1,640 kJ) |

| Carbohydrates | 3.22 g |

| Sugars | 0.8 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.0 g |

| Fat | 25.83 g |

| Saturated | 16.41 g |

| Monounsaturated | 7.52 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 0.57 g |

| Protein | 35.75 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity% DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 26%207 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3%0.04 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 28%0.33 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 2%0.27 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 7% 0.09 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 2%7 μg |

| Vitamin B12 | 50% 1.2 μg |

| Vitamin C | 0% 0.0 mg |

| Vitamin D | 3% 19 IU |

| Vitamin E | 1% 0.22 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 1.7 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity%DV† |

| Calcium | 118% 1184 mg |

| Iron | 6% 0.82 mg |

| Magnesium | 12% 44 mg |

| Phosphorus | 99% 694 mg |

| Potassium | 2% 92 mg |

| Sodium | 107% 1602 mg |

| Zinc | 29% 2.75 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 29.16 g |

| Unitsμg = micrograms • mg = milligrams IU = International units | |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Food Data Central |

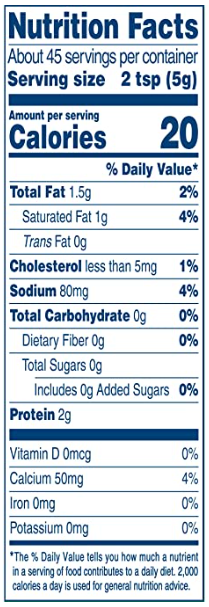

Here are the nutrition facts for grated parmesan cheese if you’re interested in that at all:

For the amount that you’ll generally be putting on your food, it’s really not that high in calories or fat.

A Little History on the Name

Also called “Parmigiano Reggiano” in Italian, parmesan cheese is an Italian, hard, granular cheese produced from cow’s milk and aged at least 12 months.

Parmesan cheese is named after two of the areas which produce it, the provinces of Parma and Reggio Emilia (Parmigiano is the Italian adjective for Parma and Reggiano that for Reggio Emilia). In addition to Reggio Emilia and Parma, it is also produced in the part of Bologna west of the River Reno and in Modena (all of the above being located in the Emilia-Romagna region), as well as in the part of Mantua (Lombardy) which is on the south bank of the River Po.

Both “Parmigiano Reggiano” and “Parmesan” are protected designations of origin (PDO) for cheeses produced in these provinces under Italian and European law.[1] Outside the EU, the name “Parmesan” can legally be used for similar cheeses, with only the full Italian name unambiguously referring to PDO Parmigiano Reggiano.

It’s has been called the “King of Cheeses”.

How Parmesan Cheese is Produced

Let’s watch a good ol’ National Geographic video on how it’s made before getting into the written part.

If you decided to watch to the end, you saw that parmesan cheese is one of the most shoplifted items in Italy. 1 in 10 of the things taken from stores by light-fingered shoppers is a pack of this popular pasta topping.

I think it’d be kind of funny to watch someone try to shoplift a giant wheel of cheese. Those ones in the video are huge, there’s no way they’d fit in someone’s pocket.

Let’s Really Get into It

Parmigiano Reggiano is made from unpasteurized cow’s milk. First, the whole milk of the morning milking is mixed with the naturally skimmed milk (which is made by keeping milk in large shallow tanks to allow the cream to separate) of the previous evening’s milking, so there is a part skim mixture.

Then, this mixture is pumped into copper-lined vats, which heat evenly and contribute copper ions to the mix.

Raising the Temperature on the Parmesan Cheese Mixture

Starter whey (containing a mixture of certain thermophilic lactic acid bacteria) is added, and the temperature is raised to 33–35 °C (91–95 °F). Calf rennet is added, and the mixture is left to curdle for 10–12 minutes.

The curd is then broken up mechanically into small pieces (around the size of rice grains). The temperature is then raised to 55 °C (131 °F) with careful control by the cheese-maker so the mixture gets heated up. The curd is left to settle for 45–60 minutes.

Collecting the Compacted Curd

The compacted curd is collected in a piece of muslin before being divided in two and placed in molds. There are 1,100 litres (290 US gal) of milk per vat, producing two cheeses each. The curd making up each wheel at this point weighs around 45 kilograms (99 lb).

The remaining whey in the vat was traditionally used to feed the pigs from which Prosciutto di Parma (cured Parma ham) was produced. The barns for these animals were usually just a few metres away from the cheese production rooms.

The Stainless Steel Round

The cheese then goes into a stainless steel, round form that is pulled tight with a spring-powered buckle so the cheese retains its wheel shape.

After a day or two, the buckle is released and a plastic belt imprinted numerous times with the Parmigiano Reggiano name, the plant’s number, and month and year of production is put around the cheese and the metal form is buckled tight again.

The imprints take hold on the rind of the cheese in about a day and the wheel is then put into a brine bath to absorb salt for 20–25 days. You won’t believe this: after brining, the wheels are then transferred to the aging rooms in the plant for 12 months.

I also had trouble wrapping my head around this one: ach cheese is placed on wooden shelves that can be 24 cheeses high by 90 cheeses long or 2160 total wheels per aisle. Each cheese and the shelf underneath it is then cleaned manually or robotically every seven days, and the cheese is turned.

Once It’s Been 12 Months

At 12 months, the Consorzio Parmigiano Reggiano inspects every wheel. The parmesan cheese is tested by a master grader who taps each wheel to identify undesirable cracks and voids within the wheel. Wheels that pass the test are then heat-branded on the rind with the Consorzio’s logo.

Those wheels of parmesan cheese that do not pass the test used to have their rinds marked with lines or crosses all the way around to inform consumers that they are not getting top-quality Parmigiano Reggiano; more recent practices simply have these lesser rinds stripped of all markings.

Traditionally, cows are fed only on grass or hay, producing grass-fed milk. Only natural whey culture is allowed as a starter, together with calf rennet.[4]

The only additive allowed is salt, which the cheese absorbs while being submerged for 20 days in brine tanks saturated to near-total salinity with Mediterranean sea salt. The product is aged an average of two years.[5] The cheese is produced daily, and it can show a natural variability. True Parmigiano Reggiano cheese has a sharp, complex fruity/nutty taste with a strong savory flavour and a slightly gritty texture. Inferior versions can impart a bitter taste.

The average parmesan cheese wheel is about 18–24 cm (7–9 in) high, 40–45 cm (16–18 in) in diameter, and weighs 38 kg (84 lb), so, it’s pretty big.

Most of the content in this article is from Wikipedia.

What You Can Make with Parmesan Cheese

As I mentioned before, there’s a ton of stuff that you can make with parmesan cheese. It doesn’t just have to be a topping. In fact, I’ve used it when making tagliolini (a fancier word for fettuccine) and as an ingredient in meatballs.

So, off the top of my head, you can use it for a lot of different things. When it comes to toppings, parmesan cheese fits nicely when sprinkled on top of some red sauce or melted on bread.

The History of the Almighty Cheese

Legend has it that parmesan cheese was created in the course of the Middle Ages in Bibbiano, in the province of Reggio Emilia. Its production soon spread to the Parma and Modena areas so even more people could experience its cheesy goodness.

Historical documents show that in the 13th and 14th centuries, Parmigiano was already very similar to that produced today, which suggests its origins can be traced to far earlier. Some evidence suggests that the name was used for Parmesan cheese in Italy and France in the 17th-19th century.[5]

It was praised as early as 1348 in the writings of Boccaccio; in the Decameron, he invents a ‘mountain, all of grated Parmesan cheese’, on which ‘dwell folk that do nought else but make macaroni and ravioli, and boil them in capon’s broth, and then throw them down to be scrambled for; and hard by flows a rivulet of Vernaccia, the best that ever was drunk, and never a drop of water therein.’[12]

During the Great Fire of London of 1666, Samuel Pepys buried his “Parmazan cheese, as well as his wine and some other things” so he could preserve them.[13]

In the memoirs of Giacomo Casanova, he remarked that the name “Parmesan” was a misnomer common throughout an “ungrateful” Europe in his time (mid-18th century), as the cheese was produced in the town of Lodi, Lombardy, not Parma. Though Casanova knew his table and claimed in his memoir to have been compiling a (never completed) dictionary of cheeses, his comment has been taken to refer mistakenly to a grana cheese similar to “Parmigiano”, Grana Padano, which is produced in the Lodi area.

Even More Fun

Parmigiano Reggiano has been the target of organized crime in Italy, particularly the Mafia or Camorra, which ambush delivery trucks on the Autostrada A1 in northern Italy between Milan and Bologna, hijacking shipments. The cheese is ultimately sold in southern Italy.[15] Between November 2013 and January 2015, an organized crime gang stole 2039 wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano from warehouses in northern and central Italy.

October 27 is designated “Parmigiano Reggiano Day” by The Consortium of Parmigiano Reggiano.

This day celebrating the “King of Cheese” originated in response to the 2 earthquakes hitting the area of origin in May 2012. The devastation was profound, displacing tens of thousands of residents, collapsing factories, and massively damaging historical churches, bell towers, and other landmarks.[18]

Years of cheese production were lost during the disaster, so about $50 million worth, reported by the New York Times, potentially threatening the livelihood of cheesemakers whose families produced this product for generations. It was Modena native and renowned Chef Massimo Bottura, who The Consortium turned to for an outsized solution to help save the cheese. Bottura’s three-Michelin starred Osteria Francescana, named the World’s Top Restaurant in 2018 and 2016 by the prestigious San Pellegrino ranking (now in its Hall of Fame) is located in his hometown near the quake’s epicenter. Massimo Bottura’s response to the situation was a single recipe: Riso cacio e pepe. He invited the world through social media and online outlets to cook this new dish along with him launching “Parmigiano Reggiano Day” – October 27